I have been working on (scent) translations over the last few months, all somehow bringing me back to the rose as raw material in perfume and flavour. My only significant encounter with roses was incredibly overwhelming. Around September 2018, I visited M.L. Ramnarain’s unit in Kannauj to learn about traditional processes of hydro-distillation - and they received me, an obscure researcher, with such kindness. I arrived around noon, just in time to see the last of the season’s roses coming in from nearby farms and to film it for Asiaville News. Even before the distillation was underway, the air was filled with a strong scent of a million blooms, like rose water as one can imagine but with a sharp green, “black pepper” note that turned muskier as one by one the furnaces were lit with wood-fire. As magical as everything looked on film, I wish viewers would focus more on how labour intensive these traditional processes are - The smoke gets so thick, so fast, we couldn’t stand in the sweltering heat for more than a second, our eyes turning red, tearing up. Meanwhile, the temperature of these multiple furnaces are simultaneously adjusted by experienced hands who patiently sit in this environment for over an hour.

At a glance, the global multi-billion dollar fragrance, flavour and cosmetic industries give an impression of unending abundance. Natural this, super ingredient that breathlessly expressed on labels! However, when one actually sees firsthand the intensive processes involved in farming, harvesting, processing, one realises how this entire sector depends on a very fragile eco-system - soil quality, increase in droughts, communal rifts, political inequity, warped dynamics with Western hegemonic powers that facilitate the open smuggling/ extraction of natural resources, and the bodies whose literal sweat we consume in our food, medicine, and perfume! Pain has a scent. Rose, vanilla, sandalwood, coffee, could all be extinct in the blink of an eye. All of these dangerous facets are intentionally hidden from us.

Shortly upon returning from this trip, I thought about formulating a rose that was not a rose - but some version of the Rooh Afza syrup. So a rose but with a slightly heightened artificiality and sugariness with notes of pepper, saffron and citrus. It sold out so fast that I found this appreciation for a “plastic” rose bloom somewhat baffling. I turned this into perfume-soap and a camphorous “Rose Sherbet” incense - the one person who bought out the micro-lot incense still raves about it to this day!

I’m tempted to reformulate this version again but with exaggerated notes of tobacco to conceptually and materially underpin the fact that India’s traditional distillation business is thriving due to the tobacco industry. Once luxurious and historically significant perfume extracts (rose, saffron, cardamom, kewra) are now used to flavour cheap mass-produced betel nut and tobacco products.

Rose in other forms

Early this year, Artist Jaishri Abichandani requested me to create a perfume for her mid-career retrospective at the Craft Contemporary museum in Los Angeles (USA). The brief stated “The scent of a paan shop (in Bombay)”. Due to how expensive shipping is, I work with clients in an unusual manner - I get them to be as specific as possible, and then I formulate the fragrance and ship - there is no sampling process in between. It is truly a leap of faith and I have always exceeded expectations!

I decided on a traditional Shamama for Jaishri. I heard a rumour that co-distilled shamama from Kannauj is actually used as a base in numerous classic French perfumes. Hidden and unmentioned in part because there is more cultural currency in advertising Bulgarian, Moroccan, Omani or Taif rose oil.

I thought to subvert this by keeping our luxuriant gulab front and centre while it dazzles with excessive hints of South Asian materials — saffron, sandalwood, cardamom and nutmeg. Once she received it, I was amazed at her description of the perfume that more than connected with her memories of childhood spent in India. Here’s how she described her experience of opening and inhaling it for the first time:

It was like walking into an air-conditioned five star hotel on a hot day in Bombay with the fragrance of a paan shop wafting in from outside. Sweet and cool, perfection in a bottle that transports me home to the monsoon seas for which I yearn.

This perfume is now worn by the artist herself and diffused in “Flower Headed Children” Mid career survey curated by Anuradha Vikram. This stunning retrospective was recently reviewed in the NYT “Protest and Pleasure: Riffs on Classical Indian Art”

This week I descended further into my genius-nonsense ideas that I have been thinking about since 2018 — these ideas are brilliant but only so if conceptually sound. What my exhibition Bagh-e Hind gave me (and by extension, the public) was a safe space for a creative and emotional engagement with South Asian history. It gave me the possibility of building an experimental multi-sensory archive together with an historian, that would expand over the years, transforming into something the public can access and appreciate as our “digital common”. Nearly a year on since our collaboration, I am still grappling with how to appropriate academic knowledge, make it accessible and through what sort of mediums?

From translating the artistic, intellectual and material culture from 17th and 18th centuries to forms of synesthesia that privilege pleasure above intellect — perfume, sound, poetry, incense, tea, edible perfume, soap — I arrive at paint pigments from this period. There is enough scholarship on how pigments were discovered, sourced and implemented, and many artists across Asia still practice this style of art. But the process of grinding pigments, mixing them with binders and using sea shells to contain them itself struck me as so visually and sensually spectacular that I wanted to recreate the effect through edible perfumed food colouring powder that one could touch, smear, taste!

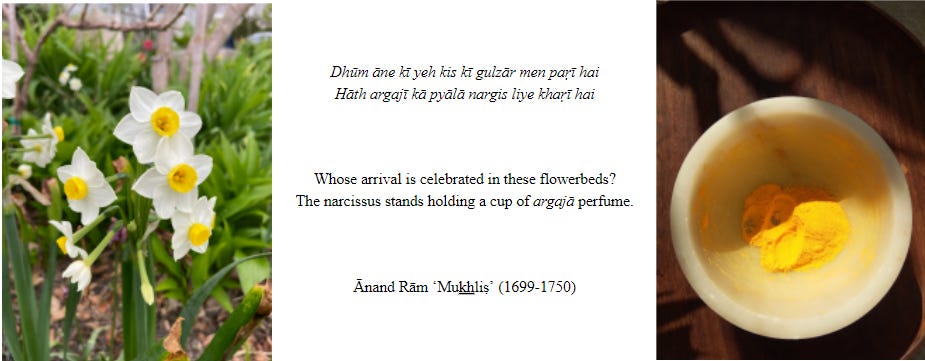

Pictured above is the first test of recreating Painting 1 as the sensation of rose-hued and rose flavoured “paint pigment”. Below is a narcissus-scented pigment-translation of the “eye” of the narcissus, abundantly grown in pleasure gardens during the Mughal era, a period during which poets waxed lyrical about its delicate beauty and one that artists defined in painterly details.

Random things on the internet:

Apparently one company in India sells pigments in a kit. The package is designed with “our” 17th century painting of Shah Jahan and his son Dara Shikoh on it. What a great idea - I am almost upset I did not think of this first!

This week Al Jazeera published a syrupy-sweet piece by Sanam Maher on the history of the century old Rooh Afza, a rose-herb cordial that “tastes like perfume” and unites the subcontinent: In Pakistan, Rooh Afza scents memories and refreshes souls

The problem isn’t synthetics, it’s naturals: The Ecowell podcast hosted a round table of industry experts to demystify the claim that natural ingredients are inherently better: Naturals in Cosmetics - Roundtable

Last week, my co-curator and research partner Nicolas Roth published a personal essay about his gardening practice in the Zine produced by The Young Propagators Society. I have come to love independently produced zines that create space for intimate expressions and are accessible at no cost, Spirit & Spice by Lover magazine is another one. This latest issue by YPS contained several other essays that outlined among other subjects, the impact of Brexit, felt firsthand by experienced gardeners, on supply chains since most of the plant/ bulb/ seed/ horticultural materials are provided by the EU. I think of this in parallel with perfumery and flavour raw materials - here today, gone tomorrow. Industries that rely on natural supplies hinge on fragile global systems, all interconnected and entangled. Climate disasters or war in one part of the globe can collapse the economy of several other nations! The consequences are swiftly felt in real time, and not as abstractions. Access Issue 8 here.

In Stock:

Rose Sherbet, reformulated with tobacco absolute ($70/ 5ml)

Rose Sherbet, incense made on request ($35/ 40 sticks)

Coffee & Frankincense, micro lot perfume ($70/ 5ml)

Tuberose, made on request

Making bespoke perfume accessible: A pet peeve of mine is how impossible and expensive it is to have a bespoke perfume made. Locating a perfumer in the first place is like coming upon a unicorn — I once looked up how much a perfumer in London charges for such a service and it was upwards of GBP 15,000. And for an additional charge, she would lock that formula for you. Anyways, I am that unicorn. Hit reply to this email to enquire about anything you wish.